Authored by Mia Bennett, Associate Professor, Department of Geography, University of Washington | miabenn@uw.edu | https://www.cryopolitics.com

[Note: this paper was presented as part of the Conservation Data Justice Symposium held in May 2024]

Environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs) have long prided themselves on their connection to the Earth. Whether that is to the planet’s lands, seas, ice, or living creatures, ENGOs often define themselves, quite literally, as grassroots organizations. Representatives spend years in the field developing firsthand knowledge of the places they seek to conserve. In addition, many aim to cultivate relationships with the people living in these places. These efforts, though, can sometimes be fraught, especially when residents oppose environmental conservation.

For all the time they spend on the ground, many ENGOs are turning to the skies. They are harnessing the power of satellite imagery taken from hundreds of kilometers above the planet to inform their campaigns, actions, and decisions. This trend is particularly clear in the Arctic – a region that is remote, difficult to access, and, in the case of Russia, which encompasses half the region’s territory, generally off-limits to Westerners since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Yet this embrace of remote sensing is not unique to Arctic ENGOs. Indeed, their skyward turn parallels the “digital humanitarianism” that humanitarian NGOs have pursued in recent decades (Burns, 2015).

In a recent paper published in Digital Geography & Society based on interviews and correspondence with six ENGOs active in the Arctic, I explain and critique how they are engaging with satellite data. The information resource is attractive to ENGOs both because it is increasingly available – often for free – and because it is seen as highly authoritative, including by governance actors in the Arctic. This includes the Arctic Council, the region’s eight countries possessing sovereign territory north of the Arctic Circle, Indigenous Peoples’ organizations, and many ENGOs themselves. The Worldwide Fund for Nature, for instance, is an observer in the Arctic Council. Greenpeace, another well-known ENGO, is not, largely due to opposition by Indigenous communities in Canada and Greenland who suffered economic harm resulting from its successful campaign to have the European Union ban the seal fur trade.

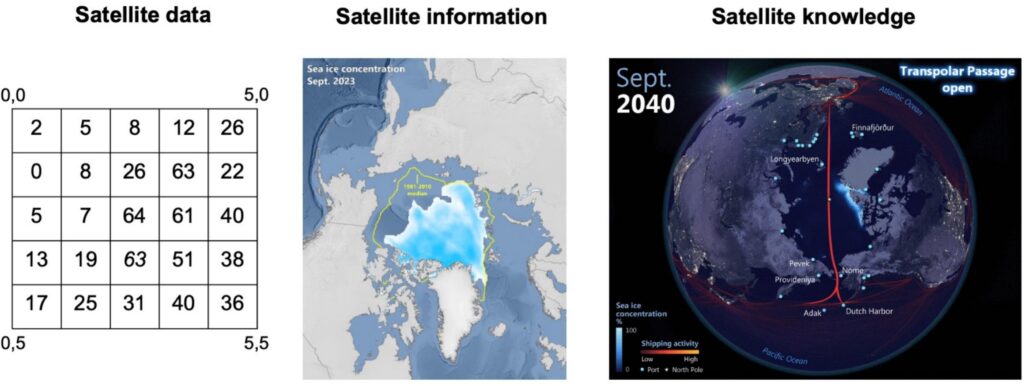

To structure my critique, I adopt the data-information-knowledge hierarchy introduced by Boisot & Canals (2004) to break satellite imagery into three categories: satellite data, satellite information, and satellite knowledge. I define satellite data as containing information about the Earth, satellite information as able to modify understandings of the Earth, and satellite knowledge as enabling its producer to act and adapt to a changing planet.

Fig. 1. Comparison of a) satellite data (as a flat binary file containing an array of numbers); b) satellite information (sea ice concentration and median sea ice extent – Ocean and land data: Natural Earth. Sea ice data: National Snow and Ice Data Center. Map: Author); and c) satellite knowledge (predicted sea ice concentration; for the full visualization, see (Bennett, 2019).

My research reveals that the six Arctic ENGOs all can access and interpret satellite data, which they generally obtain for free from publicly funded agencies like NASA, the US National Snow and Ice Data Center, or the European Space Agency. In rarer instances, they obtain data for a fee from commercial providers like Maxar or Planet, which take higher-resolution satellite imagery at frequent intervals.

A few ENGOs serve as brokers of satellite information, for instance by sharing an existing map of sea ice thickness. They often use such products in presentations or campaigns. As one representative remarked, “I’m doing some [of] our own analysis of the situation. But it’s mostly putting all the information together. And maybe, if we’re, for example, having a public speech or something like that, we would use some quotes from reports or something, so that people can think it’s really accurate information.

Only two ENGOs, however, have the capacity to produce satellite knowledge, or create novel products based on their own analysis of satellite data, which can help guide how to act within a fast-changing environment. One ENGO is working closely with an Alaska Native community to model, using satellite data, which areas may be subject to coastal inundation. The representative of this ENGO remarked, “There are some things that the community quite doesn’t quite see just because it’s so far away spatially.”

The ENGOs that possess this more exclusive capacity, which demands above all geospatial skills as opposed to community ties, may increasingly wield influence in venues where data-driven governance and decision-making are in vogue. These venues range from Indigenous communities anxious to adapt to climate change to international organizations like the Arctic Council and United Nations.

Yet even for those ENGOs that are becoming producers of satellite knowledge, even they often realize its limitations – along with the need for human, and specifically local, knowledge to direct their research. As one representative explained when deciding whether to “task” an expensive commercial high-resolution satellite, or, in other words, order it to start collecting imagery, “We will sort of call into the community and be like, hey, has the whale migration already started? Does it actually make sense for us to task now? Or are we just like, burning satellite capacity?” This is one simple way that Indigenous communities can affect satellite-based studies. Yet meaningful inclusion is needed throughout the remote sensing process in the Arctic, from designing the project to sharing the results in a clear and useful manner.

Historically, many Arctic remote sensing scientists have failed to consult the communities under their lens, though this is changing with greater recognition of the importance of local inclusion and the co-production of knowledge. ENGOs, which often started their work from the ground, may help to push more community-driven remote sensing – so long as they keep at least one foot on the ground. Changing geopolitical and economic contexts, however, may make staying grounded difficult.

The future of environmental activism in a geopolitically volatile world

Since I finalized the article in late 2024, the re-election of Donald Trump as president of the United States and the perpetuation of the wars in Ukraine and Gaza have made the world more unstable. Rising unpredictability creates an environment in which many NGOs may feel compelled to turn to satellite imagery for a variety of reasons. Some cannot access the places for which they are advocating. Others no longer have the funding to support extensive travel and long-term stays in the field. And all NGOs find themselves in a world where data and its digital bedfellows, namely artificial intelligence, are increasingly the ticket to influence and donations. This may become even more evident as a result of the fallout from federal cuts in the US to programs like USAID.

Particularly in the US, a growing proportion of the funding that remains for NGOs originates with the philanthropic organizations headed by digital behemoths like Bill Gates (CEO of Microsoft), Jeff Bezos (CEO of Amazon), and MacKenzie Scott (his ex-wife) – a phenomenon termed “venture” or “disruptive” philanthropy (Manning et al., 2020). Even the billionaire founders of internet companies long forgotten front philanthropic organizations that donate to environmental causes. Co-founder and former chief of Yahoo! David Filo, and his wife head the Skyline Foundation, a grant-making organization. As NGOs chase funding from donors with their roots in digitalization, pressure to adopt satellite data and other forms of environmental data may rise, both in and beyond the Arctic. Much as these founders sought data to make their fortunes, they may demand data to inform responses to the causes they support. The impacts of these shifts to the funding landscape on ENGOs, and on conservation and environmental justice more broadly, merit research.

References

Boisot, M. and Canals, A., 2004. Data, information and knowledge: have we got it right?. Journal of evolutionary economics, 14(1): 43-67.

Burns, R., 2015. Rethinking big data in digital humanitarianism: Practices, epistemologies, and social relations. GeoJournal, 80(4), pp.477-490.

Frumkin, P., 2017. Inside venture philanthropy. In P. Frumkin & J.B. Imber (eds) In Search of the Nonprofit Sector (pp. 99-114). New York: Routledge.

Manning, P., Baker, N. and Stokes, P., 2020. The ethical challenge of Big Tech’s “disruptive philanthropy”. International Studies of Management & Organization, 50(3): 271-290.

Link to publication

Bennett, M.M., 2025. Satellite data, information, or knowledge? Critiquing how Arctic environmental NGOs derive meaning and power from imagery. Digital Geography and Society, 8: 100116.