The International Union for Nature Conservation’s (IUCN) World Conservation Congress (WCC) takes place once every four years. It is a leading global event for setting and promoting the conservation agenda. Even though this event is not a policy-making space driven by national governments, the gathering of key actors involved in nature conservation — both those directly engaged in conservation action and those working in related fields — is remarkable and highly influential for global nature governance. As mentioned in the opening ceremony, this year’s congress emphasized multilateralism in global governance, grounded in cooperation, respect for peoples’ cultures, mutual support, and transformative conservation. Gretel Ríos, IUCN Director General, stated that “History is never neutral; IUCN chooses the side of nature, people, and justice.” But how did the discourses and dynamics between actors shape the congress conceptualization of “conservation” over the following five days? Was it clear how did the congress participants reflected on the non-neutrality of history?

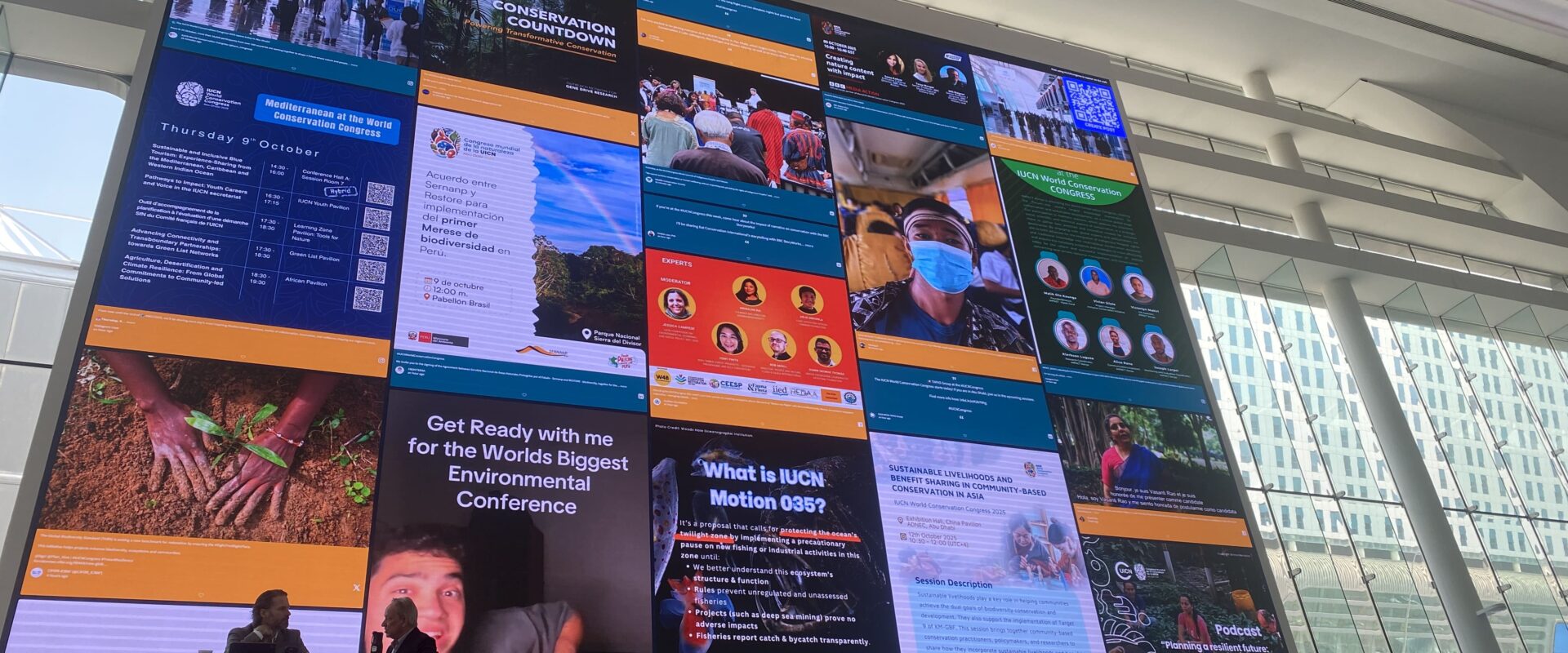

More than 1,000 events were held across the 153,678 square meters of the Abu Dhabi National Exhibition Centre, with over 50 simultaneous sessions taking place in different pavilions, halls, and spaces every two hours, from 8:30 a.m. to 9 p.m. Gathering diverse audiences for each event was not an easy task — and in some cases, not even possible. As a member of the public, participating required taking an in-depth look at the program, preparing in advance (but not too early, as presentations changed daily), prioritizing among multiple concurrent events, having a good command of English (since the program and most presentations were in that language), and using one’s time wisely while moving from one space to another.

Having made that disclaimer, and acknowledging that it was not humanly possible to attend most events, finding one’s space was crucial. Even so, key trends emerged throughout the WCC program. Some of these revolved around finance and technology for conservation, and how these could converge inclusively. Technical approaches to achieve this convergence were mainstreamed across different halls and pavilions, but often remained separated from one another, attracting specific audiences clustered by geography, language, sector, or affiliation. This also meant that participants were often surrounded by like-minded people in terms of how they conceptualized conservation, instead of discussing fundamental differences. It was difficult to find spaces dedicated to conversations from different worldviews in a clear and direct way outside of the Reimagining Conservation Pavilion, a space hosted by the IUCN´s Commission on Environmental, Economic, and Social Policy (CEESP) in collaboration with diverse partners, including CONDJUST. Spaces for crossing over different perspectives and seeking to challenge the status quo were not necessarily at the center stage.

However, one interesting discussion stood out between the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and Indigenous initiatives supported by this fund through the Inclusive Conservation Initiative. Indigenous counterparts critically pointed out that the challenges they face in pursuing their initiatives often begin with the opposition of their national governments to acknowledge and support Indigenous rights. Conservation and climate funding do not exist in a vacuum. Nevertheless, funders’ expectations are already set, funding themes predefined, and technical pathways and application requirements established. At the same time, another major issue arises from the misunderstandings that occur when discussing what “conservation” means among different stakeholders. International cooperation should recognize that epistemic and historical conflicts are deeply intertwined with conservation interventions.

In the Indigenous Pavilion, those same claims resonated across the events taking place in that space. This pavilion was very special — it served as a gathering hub for anyone interested in discussions around Indigenous self-determination, rights, and recognition from across the world. These themes were inherently transversal to conservation action, as emphasized by the pavilion’s speakers. In fact, these themes were the building blocks of conservation action from the perspective of the Indigenous leaders taking the stage. Strong criticisms were voiced against extractivism threatening Indigenous territories, as well as against conservation practices that separate peoples from their lands. Their proposal for achieving the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) commitments was clear: to recognize Indigenous territories and position this recognition as the first pathway of the global conservation agenda. To make this possible, they proposed creating an Indigenous financial body that would allow Indigenous Peoples to become autonomous from other funding mechanisms that require them to adapt to mainstream conservation — rather than adapting funding to Indigenous ways.

I am left wondering how other events and speakers engaged with the idea of “choosing the side of people, nature, and justice,” as mentioned in the opening ceremony. I wonder whether historical and political approaches to justice were even acknowledged in spaces where technology was being mainstreamed as a major opportunity to advance conservation. I wonder if the different discussion spaces could have, somehow, truly integrated diverse groups of people and epistemic communities on equal footing. Would fostering deeper conversations that question the global systems we live in could have change the meaning of the congress?