Authored by Jocelyne Sze and Laura Sauls

Conservation increasingly relies on big spatial data (including global maps) for decision-making, but uncritical adoption may hinder just and effective conservation outcomes.

[Note: this paper was presented as part of the Conservation Data Justice Symposium held in May 2024. This blogpost has also been cross-posted on the Just Earth Observation project blog.]

From its more localised origins in natural history and field ecology, biodiversity conservation has grown into an interdisciplinary science with a global outlook. Part of what gives conservation this global perspective is the use of maps, particularly in being able to create visualizations at the planetary scale. Scholars and practitioners embrace digital technologies, including the use of large-language models and other Artificial Intelligence (AI), to help collect, process, and analyse spatial data at large scales to improve conservation decision-making and conservation outcomes (Runting et al., 2020). The fields of data justice, critical data studies, and critical GIS can challenge the potential harms and injustices that arise from the discourses, practices, and infrastructures around big data (Nost and Goldstein, 2022). Big data are not well-defined, but tend to have the following characteristics:

- Large volumes of data

- Generated or made available at high frequencies

- Of different types and from different sources

- Exhaustive (rather than sampled)

- Often requiring new tools and high computational power for processing

It also refers to the way data are understood and used – a belief that quantification and datafication can capture reality accurately (for example, the human footprint map as capturing human impact (Watson et al., 2023) or the development of metrics for measuring biodiversity (Burgess et al., 2024) . Building on these fields, we ask how big geospatial data may enable and hinder effective and just conservation science, policy, and practice.

Turn to big geospatial data in conservation

In the last couple of decades, satellites and satellite imagery for earth observation have become more available at the same time as increased efforts to collect global biodiversity data (e.g. eBird, iNaturalist citizen science platforms). Combined with the framing of biodiversity loss as a global problem requiring global solutions, and the ability to obtain biodiversity data at planetary scales, spatial data, in particular global maps, have become a central tool of conservation science. We posit that the emphasis on production and use of big geospatial data derives from its perceived policy relevance, publishability in high-impact journals, and trends towards open-access data making it easier and cheaper to conduct such analyses in global north institutions.

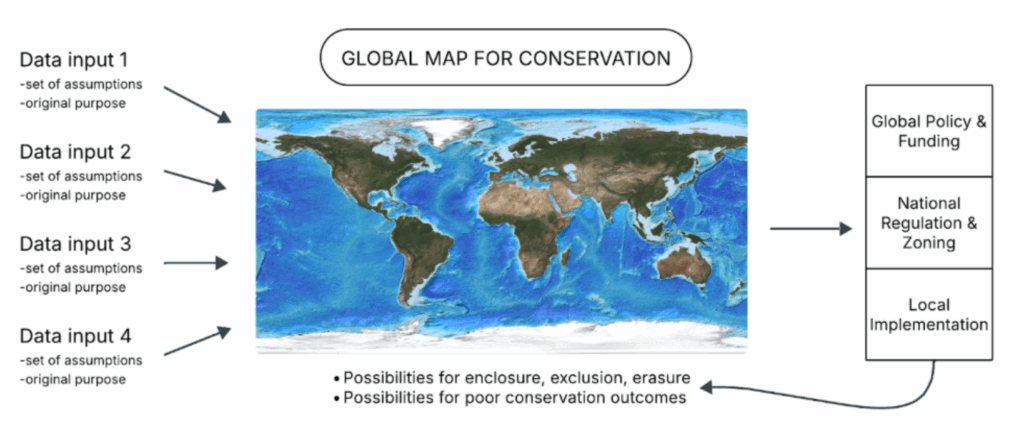

Big geospatial data and related tools for conservation are also in use by researchers who have been able to combine such data with socio-economic data as well as in more participatory processes for supporting Indigenous and local voices through spatialized data (e.g. use of drones to defend territorial rights; Sauls et al., 2023). These types of benefits are well worth noting, but there are potential drawbacks as well. A feature of big data use is the repurposing and combining of data from different sources and provenances; however, there are real risks to such agglomeration (Figure 1). Without adequate information on how the data were collected, produced, and processed for analysis, other users will not be able to understand what biases exist within the data and, thus, not be able to use them appropriately. This is especially so with the increasing use of machine learning models, for example, to map poverty from Earth Observation data but these maps fail to accurately represent local contexts (Watmough et al., 2025).

Figure 1. The combination of different data sources to produce a global map can have social and ecological implications at various scales and risks resulting in socially unjust and ecologically ineffective outcomes. Figure reproduced from the paper.

Assumptions in decision-making when using and processing the data can also reproduce biases, such as the perception that all human influence on the environment is negative. Interpretations of land use from land cover, a common element of geospatial analyses, can also amplify historical prejudices, for example, that grasslands are wastelands and unproductive (Lahiri and Reddy, 2025), or that population and livestock are threats to biodiversity (Chignell and Satterfield, 2023). Big geospatial data use that is not embedded in interdisciplinary teams or in coproductive ways can result in such assumptions remaining unchecked and spread through subsequent maps, becoming embedded ‘knowledge’ about reality.

What are the risks?

In this context, incorporating more and more data might give a veneer of truth, but global maps are still always partial representations (Malavasi, 2020). While they seem authoritative, maps only work because they simplify complexity, flattening knowledge and information, and amplify their creators’ particular ways of understanding the world (ontology) and what knowledge and knowledge production (epistemology) are. As such, big geospatial data can further center Global North perspectives (because they tend to be the ones making these global maps) at the expense of local knowledges that may be more relevant and appropriate for the area or topic (Cheyns et al., 2020).

This is especially because the kinds of information or knowledge that are amenable to be produced in map form tend to be quantitative, emphasising, for example, economic values over non-economic values. Thus, over-emphasis on the utility and centrality of maps can result in losing multiple and overlapping ways of valuing land and territorial relations. Even with participatory mapping, if control and ownership of the subsequent data fall outside the community (see: CARE principles), promoting more mapping could become extractive (for the benefit of the global scientific community), rather than coproductive or liberatory. Providing communities with data on open-access platforms to analyse for their own territories may also not be the most equitable or ethical solution, if the data are not fully understood by communities or not contextualised to their area.

We should be wary of contemporary, uncritical narratives demanding ever more data collection, especially through the use of AI and other technological advances. More data being collected, especially remotely, can increase the sense of surveillance and control of authorities over communities. The increasingly high resolution of satellite imagery available now (of 10 cm per pixel!) raises concerns over the potential for personal identification and the lack of Free, Prior, Informed Consent given by any of the world’s population. The use of these data for decision-making by external actors, void of cultural, political, and social contexts, can result in negative implications for communities, harking back to past exclusionary conservation policies.

Towards just and effective use of geospatial data in conservation

The crux of our argument is that all conservation researchers would benefit from carefully considering how and why big geospatial data are used in conservation science. More data and the use of digital technologies on their own will not make for better or more effective conservation decision-making, let alone just conservation. Big geospatial data, in many ways, reinforce separation between humans and nature, and we should consider more carefully how we can collect appropriate and useful geospatial data, develop research and indicators that support community rights, and advance inclusive and socio-ecologically just visions of conservation.

Link to publication

Sze, J.S. and Sauls, L.A. 2025. Prospects and perils in the geospatial turn of conservation. Conservation Biology, 39(6): e70145. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.70145