The First Conservation Data Justice Symposium Participants, Girona 2024

Preamble – what were we trying to do

The excitement of working in the field of Conservation Data Justice is its newness. This is a topic that brings people together from different disciplinary backgrounds, who have not had the chance to work together before. That carries with it a danger – we forget our antecedents. But there is an energizing freshness to this collective endeavour.

That energy and excitement was well captured at the end of May 2024, when a group of scholars and practitioners examining different elements of Conservation Data Justice convened in a former farmhouse close to Girona to share their work and experiences. This meeting was planned well in advance: an energetic organising committee (Lourdes Vera, Laura Sauls, Rose Pritchard, Eric Nost, Jenny Goldstein, Lauren Drakopulos and Dan Brockington) met over a year beforehand to draw up the call, inviting participants to join and to share their papers well before the meeting began. Consequently, when we the Symposium invitees met we combined researchers (from all career stages and four continents) as well as two practitioners, and discussed 18 papers (illness and visa issues preventing two others).

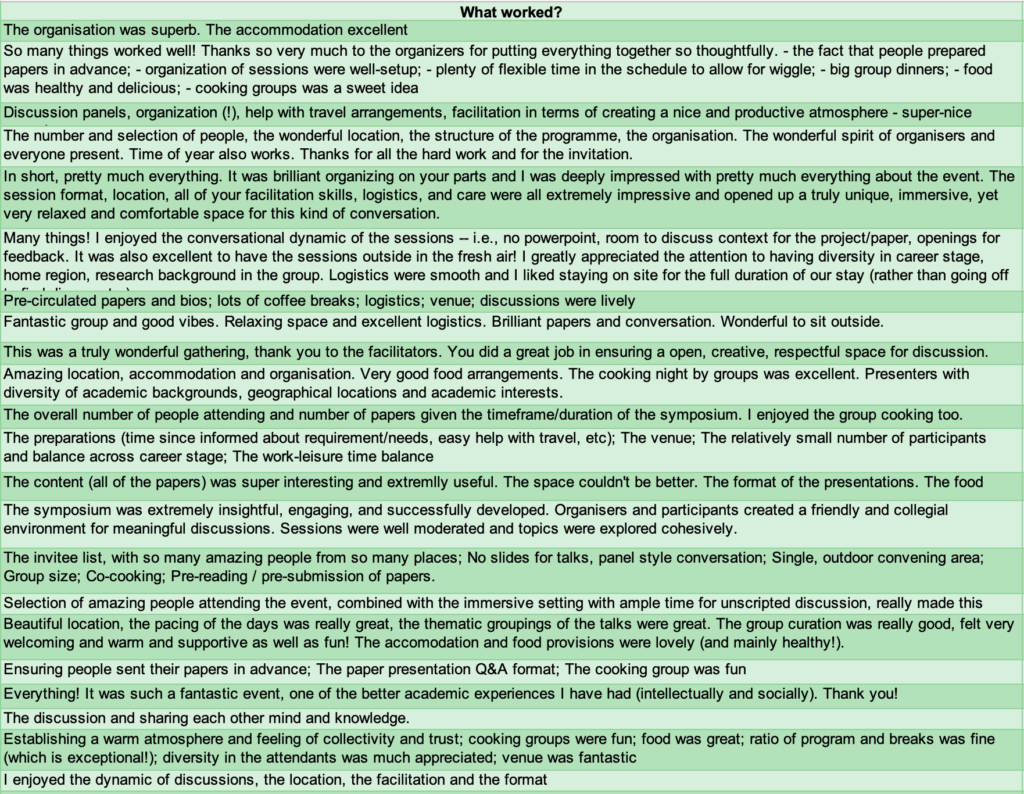

The general consensus seems to be that this one went well (see the ‘what worked’ feedback at the end). In part this was because of the generosity of the funders, for which our thanks to the ERC, and the participants who funded their own travel. In part it was because of the fantastic logistical support of the ‘OPI’ project team in Barcelona. And in part because we were meeting in Catalunya. This is a beautiful place and also meant it was possible for attendees to stay a bit longer in Barcelona, or out in the Pyrenees before or after the meeting (Fig 1). So, when the organisers invited people to a most-expenses paid trip to join this gathering, most people rather quickly said ‘YES!’. And that was before they saw that our venue had swimming pools (Fig 2).

Fig 1: The Pyrennean workshop debriefing team in action

Fig 2: If it makes you feel any better, it was too cold to swim in this

One of the blessings of the meeting was its spirit. The organising committee had found a venue early on that allowed us to meet on a large, covered veranda with beautiful views and cooling breezes (Fig 3). This did much to lift the mood. So did the practice of cooking for ourselves on one evening (Fig 4). But really the generally receptive spirit of enquiry and openness was fostered by the participants themselves and their preparation and enthusiastic engagement with the pre-circulated papers.

Fig 3: A compelling speaker means no one is distracted by the view

Fig 4: Every house in Catalunya must have a convivial balcony

We had hoped for a productive meeting – and we got that with bells on, not only due to the discussions during the gathering, but also due to the number of new humans represented amongst the organizing committee and participants. Some organizers and invited participants, had to drop out because of newly arrived, or imminently expected, babies. Others arrived with little ones in tow (or shared news of impending new arrivals at the meeting!). A feminist academia requires thinking about how to accommodate family commitments, and we adopted as inclusive an approach as possible, meaning arranging good baby care facilities, balancing sessions with feeding times and sorting out pumping stations.

What actually happened

All papers were presented in plenary, without powerpoint, and discussed with the whole group. We set time aside for discussing emerging themes, as well as some relaxation time before evening meals. The last day was mostly devoted to group discussions. We had, deliberately, not tried to set up a concrete product or target a special issue of selected papers for this gathering. Rather we wanted different themes and topics to emerge without an end format in mind. Here are some of the themes which emerged:

First, how can we make better models and better maps? Sometimes, we might do so by bringing disparate data into conversation with each other, and sometimes by entire new processes of data collection. Here we were particularly fortunate that this meeting brought in people working on other funded projects. Javier Fajardo shared work in progress as part of the SNAPP project exploring Social Implications of 30*30, led by Chris Sandbrook. His paper examined the social and economic consequences of different ways of reaching the 30*30 target, as captured by a variety of socio-economic data. Marina Requena presented findings from her attempts to incorporate biodiversity feedback loops into agricultural models as part of the CONDJUST project. She observed that some models used to prioritise restoration can assume a linear relationship between intensification and yields. This boundless optimism is not wise and it may be necessary to acknowledge that yields can decline with excessive intensification in part because of the loss of biodiversity that is useful to agricultural activity. Marie Pratzer and Tobias Kuemmerle shared an extraordinary paper from the SYSTEMSHIFT project that outlined a process for turning a land cover map into a land use map. Working in the Bolivian Chaco they produced land use categories that are allowed to overlap each other, providing a much more sophisticated picture of what social activities are taking place in apparently similar looking spaces.

A key concern for many was to identify the ways in which bias and distortion can appear systematically in conservation data and algorithms. This was explored by Hilary Faxon and Millie Chapman for the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, showing, inter alia, how colonisation still affects knowledge production about biodiversity. Ryan Unks outlined ways in which degradation can be perceived in pastoral landscapes but yet ignore some of the basic rainfall driven dynamism that dominates semi-arid grasslands. Jocelyne Sze and Laura Sauls examined how methodological choices and epistemological assumptions of maps can afflict injustices in conservation’s geo-spatial turn. Carl Boettiger asked ‘do algorithms have politics?’ (they do) following Langon Winner’s foundational paper on the politics of artefacts, and then proceeded to develop a fascinating history of the development of AI and the politics of the choices that entailed.

Another aspect is who is producing these data. Wilhelm Kiwango’s paper pursued this theme, outlining a research agenda for exploring the inequalities in the production of conservation data between the global North and South. Nick Record and others (including Lauren Drakopulos, Lourdes Vera) considered the biases in harmful algal bloom data and how the collection and production of these data re-inforce global inequalities. The patterns they found reflect and potentially reinforce the existing economic and political relations that underpin global ocean stresses, with monitoring and knowledge generally concentrated in high-GDP, northern North Atlantic nations. Danilo Urzedo’s work developed an interesting twist in this focus on bias and distortion. His paper on payments for ecosystem services in Brazil and Australia identified diverse sources of systematic bias such as, in the case of Australia, imagining idealised landscapes that did not include aspects of indigenous land management. But he also showed how addressing that bias can result in potentially empowering solutions to marginalised groups.

Another collection of papers were concerned not so much with the data themselves as the ways in which the technology itself has to be understood and deployed within particular social contexts. Munib Khanyari presented work exploring the ethics of camera trapping used in monitoring snow leopard conservation in the Indian Himalayas and how to work with communities in whose lands camera traps must be placed in socially just ways. Naomi Millner shared work on the ‘four figures’ of drones and the surprising ways in which their surveillance potential can be welcome to rural peoples. Jen Silver traced key moments in the development of the Canadian Radarsat Earth Observation programme and reflected on what satellite technologies might mean for biodiversity governance in Canada. Joycelyn Longdon described the way her research on bioacoustic monitoring had to be completely redesigned, in welcome ways, as she negotiated complex politics surrounding use and access of forests in Ghana. Through participatory acoustic monitoring engagements, Joycelyn discussed the approaches to trust-building necessary to create equitable and engaged collaborations. She argued that, in order to move from concern to meaningful consent in a way that centres community needs, researchers and practitioners must respond to suspicion, address agency, centre community knowledge, and demonstrate data practices.

There were papers which explore the social uses of data in particular communities. Putri Damatashia and Paul Thung outlined a way in which conservation data are operationalised by Planet Indonesia. They analyzed how concerns about data justice inform Planet Indonesia’s work and described the NGO’s strategies and practices for addressing various justice dimensions of data production and use. Mia Bennett traced the evolving use of satellite data in the Arctic by diverse NGOs. A particular focus here was how these data might displace indigenous forms of knowledge. Jocelyne Sze and Laura Saul’s and work on geospatial data and conservation also showed how conservation communities are using those data.

Finally, there were papers that defied easy categorization and represented the broad range of disciplinary and epistemological approaches and the normative politics that conservation data justice might capture, such as work by Eric Nost, Lourdes Vera, Tim Schütz and Caleb Scoville and colleagues (including Lily Xu and Melissa Chapman). The former clearly incorporated feminist STS and concerns over embodiment and care with questions of justice; the latter built on classic work in STS and computational sciences. The latter explore the theories of contributory autonomy that are implied in the construction of complex data rich models where ‘the deliberating decision-maker is eclipsed by the end-user’. Though less explicitly concerned with conservation, these manuscripts clearly implicate key issues arising in other papers and speak to the need for ongoing, cross-cutting conversations.

So what next?

All in all it was a good gathering. But there are many ways of improving it. Greater representation of scholars beyond the majority world would be one key improvement. And we will need to think hard about how to curate and bring together the ideas in the most productive ways. Finally, while we were surrounded by birdsong, as one attendee observed that there were no large charismatic mammals in sight at all. Indeed – and (although people in one house saw deer) this is our bad. We had to make do with the babies present instead. The babies made remembering that vital point you were about to mention really hard, no matter how important you yourself actually are (Figures 4 and 5).

Fig 4: Move over: this meeting is not big enough for the both of us

Fig 5: Mmmmm. That pen is literally delicious

Another piece of useful feedback is that we need more of these meetings. That we will act on. This is after all just the first meeting. Conservation Data Justice is a growing field with a lot more work to come (including a growing CONDJUST team, Fig 7). It may be hard to match the pleasures of the meeting just held (as the feedback below suggests). However, with an epistemic community that is intent on providing the sort of good-spirited engagement that set the tone on this occasion, and Catalunya’s propensity to provide amazing beauty and good weather, we can hope to emulate it.

Fig 6: What worked (and of course we collected views on things that did not work, but this blog was meant to end on page 5, so now there is not enough space).

Fig 7: CONDJUST in our natural habitat